Flexibility Vs. Stability

- marketingc8

- Nov 13, 2025

- 2 min read

You know how it goes. You take your body for granted when it works. Right? But when something starts to hurt, you mind starts to wonder.

How did that happen? What did I do? Is that something the body can fix—by itself? Do I need a doctor? Or physical therapy? And—will it go away? What if I ignore it?

Well, in the case of the writer of this anatomy-related blog, it’s the shoulder.

More specifically, and we quote from the report following an MRI: “There is a torn posterior inferior labrum with adjacent small para labral cyst measuring 7 mm.”

This is a tear in the soft tissue (labrum) that lines the bottom and back of the shoulder socket (glenoid).

At least, that’s the detailed issue. To the owner of this joint, the issue simply screams “shoulder hurts!”

There are, in fact, many different kinds of shoulder joint injuries. There’s tendinitis (inflammation of the tendon). There are tears, and those can be either partial or full-thickness. Some tears are sudden, from injury. Some are from long-term wear and tear. There’s also bursitis—inflammation of the bursa sac that cushions those tendons.

The rotator cuff, in fact, is four muscles—supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. The shoulder is often considered the most complicated joint in the body for a number of reasons including the shoulder’s high degree of mobility. Go ahead, stand up and move the arm around in all the ways it will go—front to back, up and down, reach this way, reach that way, rotate the arm one way, rotate it back the other. Every arm motion is shoulder-dependent.

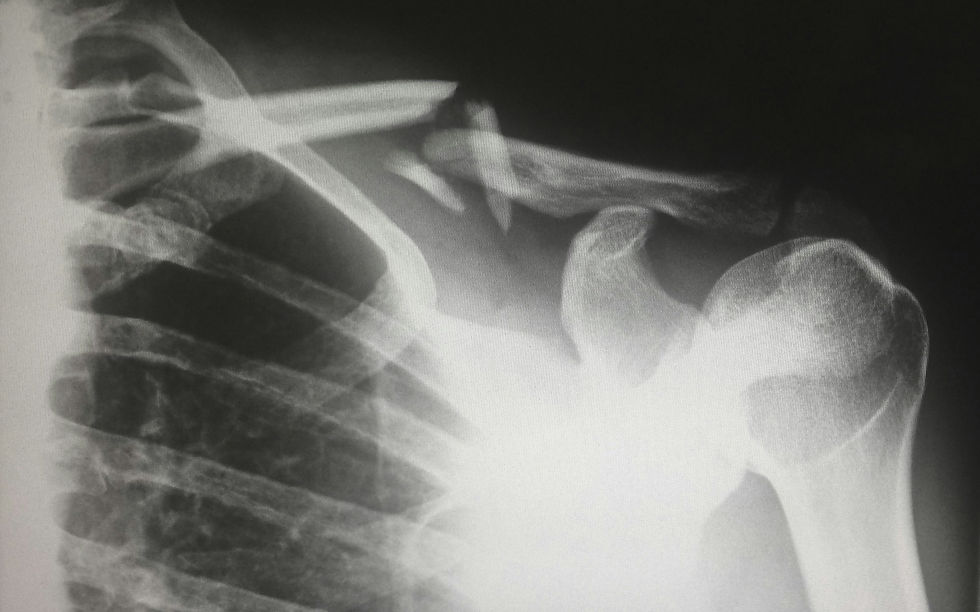

The shoulder complexity is also due the three bones—the humerus, the clavicle, and the scapula—and the two joints (glenohumeral and acromioclavicular). For an excellent animated look at the shoulder, here’s a good video:

Go ahead, blame evolution.

Unlike the deeply-socketed hip joint, the shoulder’s ball-and-socket joint is shallow, making the humerus susceptible to dislocation (and resulting in strain on the surrounding muscles, tendons, and ligaments).

You can trace this back to our early primate ancestors when we were climbing and hanging in trees. Our ability to extend our arms fully above our heads was a crucial braking system for descending trees safely. We needed that range of mobility and, when we started hunting and gathering, we needed the arm to throwing things that would kill our prey. Thus, the more shallow, and more versatile, joint. (Our shoulders are very similar to that of chimpanzees.)

The bottom line?

“Most flexible” equals “least stable.”

As the old saying goes, there’s a price for everything.

.

.

.

.

Comments